- Home

- Greg Tesser

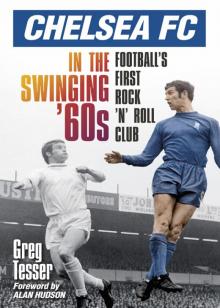

Chelsea FC in the Swinging '60s Page 3

Chelsea FC in the Swinging '60s Read online

Page 3

All-ticket affairs were (apart from the FA Cup Final and England v Scotland battles that is) non-existent. But for a variety of reasons, this Cup tie captured the imagination of the London public to such a surreal extent that traffic on the Fulham Road became gridlocked as more and more people attempted to pay at the gate. Chaos reigned supreme!

Exactly 70,123 packed into the decrepit old lady that was Stamford Bridge circa 1964. A host of season ticket holders, most notably Tory Transport Minister Ernest Marples, were denied access. Mr Marples, the man behind both the M1 Motorway and Premium Bonds, was, understandably, more than just a wee bit peeved.

The game itself was a real one-off. It was a strange sight; the ‘yoof’ of blue-shirted Chelsea starlets trying to knock the elder statesmen of North London off their elevated perch. The Blues, inspired by Terry Venables – ‘Docherty’s Diamonds’, as they were called – buzzed around Spurs like a swarm of blue bees on speed. There was only one team in it.

Despite missing a penalty, Venables had a great night, and it came as no surprise when little Bert Murray found the net. Bobby Tambling added a second, and the cheers were heard all the way down the King’s Road to Sloane Square and beyond.

I got to know Terry later when acting as Rodney Marsh’s agent; in fact I did a few journo things with him. I also attended a benefit dinner he had organised (I’d given him a cheque for £25 whilst reclining in Marsh’s brand-new Lotus Europa) in aid of Queens Park Rangers central defender Frank Sibley, who was forced to retire at the tender age of twenty-three because of a serious knee injury.

As the food disappeared and more and more champagne flowed, I mentioned the 1964 Cup-tie. His eyes lit up as he became more and more animated, and he told me it was one of those matches that remained in the memory forever. I am sure by this time my speech had become slurred and as thick as school custard, and I probably had one of those idiotic smiles on my face, but he answered my questions seriously, yet at the same time his eyes laughed – he had a real touch of the showbiz about him.

It was 1964 and the Chelsea v. Spurs epic was indeed a landmark game. For years, the ‘End of The World Is Nigh’-merchants had been predicting that the decline in football attendances would continue at an alarming rate, but here was an example of football capturing the public’s imagination; in many ways it was a sign of how London was beginning to swing and become the chic capital of the world.

Chelsea finished the season in fifth spot, seven points adrift of champions Liverpool. As fans, we knew we were on the cusp of something big – something momentous in the club’s chequered history. It could take a few years, but the Bridge was fast becoming the buzzword in London’s football circles. And the Soho waiters, those connoisseurs of all things Chelsea football, were often seen leaving their posts in droves to cheer on Docherty’s men – they knew the ‘days of wine and roses’ were not far away.

As for me, I was about to enter the labyrinths of Soho, the Blues and rock ’n’ roll, and Andrew Loog Oldham, the man known as the fifth Rolling Stone, who wore green make-up – in short, the land of the artful dodgers and fornicators and fixers who frequented Tin Pan Alley.

FOUR

THE YARDIFYING YARDBIRDS

AND NOT FORGETTING CHELSEA

In 1964 there was more blues music being played in Kingston and Surbiton than Chicago.

So, as an eighteen-year-old, giving a ‘V-sign’ to any thoughts of Oxford or Cambridge – they wanted me but I didn’t want them! – I bought a pair of expensive Chelsea boots to go with my Italian shades; made sure I had my soft packet of Disque Bleu fags neatly tucked into my Lord John jacket; put on my solid gold ID bracelet, making sure it hung limply – almost apologetically – on my wrist à la Jerry Lee Lewis, and announced to my father that I wanted to be ‘another Andrew Loog Oldham’.

Oldham was all flamboyance and Hollywood kitsch; you could say he orchestrated his own presence. He drove round London in a shiny American limousine – a Caddy or some such – making calls on his car phone. On his well-defined, almost beaky nose were green-tinted spectacles. He had what became known as ‘attitude’. It was all an act, of course, and he knew it was all an act, but he revelled in it; the job of hauling in huge quantities of the folding stuff was for him like some massive game of Monopoly.

Andrew – I never imagined anyone addressing him as Andy – was a narcissistic hustler. In 1963, aged just nineteen, he had helped publicise Bob Dylan’s first UK tour and had also assisted The Beatles’ manager Brian Epstein. Then in the spring of ’63 his whole life changed when he saw a group sing blues and rock.

Now this group (we didn’t call them bands then) had already built-up a Home Counties following, thanks to the efforts of a wild Georgian (the birthplace of the odious Joseph Stalin), with a Swiss passport named Giorgio Gomelsky. However, no contract had been signed and when the cocky young Oldham turned up and spieled, the group put pen to paper and The Rolling Stones were born.

Our family business, Studio Torron, had first seen the light of day back when London was recovering from the Blitz – 1942 to be exact. It was a company specialising in the art of silk-screen printing – cinema posters, government posters and the like.

It thrived, and my father soon had a clientele list of interesting and often outlandish characters. He built up a rapport with film director Roman Polanski, and in so doing produced dynamic posters for two of Polankski’s acclaimed movies, Knife in the Water (1962) and Repulsion (1965).

Later in the ’60s, he embarked on the idea of producing pennants – small triangular posters – of headline pop acts including Peter and Gordon and (most notably) The Rolling Stones. And so he met Andrew Oldham and his business partner Peter Meaden, and so did I.

Talking of Meaden, despite his untimely death at the age of thirty-six, his influence remains to this day. Another exhibitionist and hustler, he is often given the title ‘The Mod Father’ or ‘Mod God’ by modern rock-culture historians.

Probably his biggest claim to fame was discovering The Who. He changed the band’s name to The High Numbers, and they released a record, ‘I’m The Face’, aimed at their Mod fans. The disc bombed, with most of the copies being bought by Meaden himself. He later lost control of the group, and teamed up with Oldham. The High Numbers reverted to The Who, and the rest, as they say, is history!

Meaden never struck me as a contented man, and sadly, in 1978, he died of a barbiturate overdose.

Anyway, my father got on really well with these two people, and when I was introduced to Oldham, I literally shook with excitement.

It was at our house in Hampstead, and Andrew and Peter sat reclining languidly in the sitting room smoking cigars. I attempted to do the same, but forgetting to snip off the end, I failed miserably. I even tried to get a flame via the electric fire. Boy did I feel a fool! However, thankfully Andrew was more than interested in my record collection, which was pretty way-out, made up as it was by a whole clutch of LPs sent to me by my Aunt Trudie from America.

To say The Rolling Stones’ manager was interested in these records would be an understatement. However, he never seemed to display any emotion in his waxwork-like face, which at times resembled Mr Sardonicus in that cult William Castle horror film of the ’60s of the same name – frozen in the manner of a Botox OD.

Two Lavern Baker albums particularly fascinated him, as he scrutinised them in the manner of a pathologist examining a body found in suspicious circumstances, and he asked me if I’d lend them to him. I agreed, but never saw them again. How he utilised them, I’m not sure, but rest assured he would have done.

Having endured my ‘audition’ with Andrew Oldham, I set about aping him. But I was, and still am, a romantic, and I found this hard to achieve, for his brand of wheeling-and-dealing did not come naturally to me. So, any outgoing cockiness or overconfidence on my part was one big overblown charade. However, I remained undaunted, and set about ‘finding’ a rock group of my very own. My Chelsea boots were at long last doing some walking!

I

got to know Pete Bardens through a guy called Dave Ambrose. Bardens was the leader of The Cheynes, a progressive band appearing regularly on the under card at The Marquee in Soho’s Wardour Street. A nervous, shy man, Bardens was not an easy man to approach, but despite his diffidence, he did indicate a modicum of interest in my becoming their publicity manager. So I jumped into a black cab and made my way to that unapologetic haven of hedonism to see them perform live.

John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers topped the bill that spring evening in 1964, playing their unique brand of blues. The Marquee was by no means packed, but it was full enough, and that particular aroma of cigarette smoke and sweaty bodies, mixed with a fragrance of whisky and coke, so evocative of 1960s clubs, gave it a special ambience.

The Cheynes were good – maybe not sensational – but they looked disaffected and rebellious enough to be emblematic of this cultural change; this youth-based rejection of values that had remained entrenched in British society since the Depression years of the 1930s.

I did my best, but essentially Bardens was a loner, a man who wore the total rejection of all things commercial on his sleeve – very similar in character to Chelsea footballer Charlie Cooke. He was certainly not driven by money. A bit later Bardens must have changed, as indeed seemingly did Cooke.

Having left The Cheynes, Peter Bardens went on to perform with some of rock music’s most iconic performers, including Van Morrison in Them and Rod Stewart, Peter Green and Mick Fleetwood in Shotgun Express. He sadly died in January 2002, aged fifty-six.

Anyway, I did a little bit of PR for The Cheynes, but realising there was no future in this I somehow wangled a job in ‘the British Tin Pan Alley’.

Bob Baker was tall and blond. He wore pinstripe suits, and somewhat bizarrely, Chelsea boots. He had been a whiz-kid with Warner Bros, but the lure of the burgeoning British music scene proved too strong, so there he was in the spring of 1964, heading a PR organisation at No. 7 Denmark Street called Press Presentations. This was a new company, but several of its clients were potential headliners, with Georgie Fame, Screaming Lord Sutch and The Savages, The Yardbirds and Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band, the prime potential money-spinners.

Now, Denmark Street circa 1964 was not only a cosmopolitan place, with its close proximity to the drinking dens and fleshpots of Soho; it was also the hub of the British pop music industry, known as ‘the British Tin Pan Alley’ (there already being a Tin Pan Alley in New York) – a microcosm of the changing landscape of British culture.

Having rejected university, and failed rather miserably to emulate Andrew Loog Oldham, I had no choice but to swallow my pride and get a job – but what a job it proved to be!

Bob Baker was regarded as a highly effective wheeler-and-dealer at Warner Bros, and there was no doubt he was ambitious, almost obsessively so. However, his aspirations – even to me, a rookie eighteen-year-old – seemed sometimes to verge on the fantastical.

My father had ‘done deals’ with him, and following his persuasive tongue, the enigmatic Baker agreed to take me on as his number two. He had the experience, but my youth gave me a huge advantage over him. He was stuck rigidly in the 1950s, whereas I was part of this new generation – a generation that was doing its utmost to bring colour to a monochrome London – a London that was finding a new identity as bands all over the West End played the blues and reinvented rock ’n’ roll.

It is a Monday morning in late March 1964. The time is 9 a.m. The location is La Gioconda, an Italian café on Denmark Street, specialising in the all-day breakfast many years before such a culinary creation was known to the British public.

Now, the ‘Gio’ was, to young eyes, a wondrous place. To your left could be George Harrison tucking into egg on toast, while at the same time behind you, Eric Clapton or John Lennon or the-then unknown David Bowie were filling up on beans and strong coffee.

At a table, tackling a huge plate of baked beans sit three people, one, a wide-eyed eighteen-year-old – the other two, more cynical men in suits. The younger of the threesome is told he would soon be meeting some of the company’s more illustrious clients – the musicians and their managers. Little then did this teenager appreciate what was in store for him; the gangsters, the dances till dawn, the drugs and the drink and the whole madcap stuff that were to dominate his life for several years, not forgetting trying to find time to make for Fulham Broadway and Stamford Bridge to cheer on Chelsea.

Having acquainted himself with his office and met the secretary Ursula, a young lady with the voice of Wendy Richard and the face of Sandie Shaw, he embarks upon a series of meetings with his boss, Bob Baker. Lucky Strike gaspers are smoked incessantly as ideas are thrown around. As the air gradually becomes thick with tobacco smoke, the youngster listens as the older man spouts loads of meaningless words about exposure and promotion and PR and publicity. In the boy’s opinion all this is old hat – it has absolutely nothing to do with what is going on in the country, or more specifically, what is happening in London.

As his eyes glaze over, he falls into a reverie, but reality returns when Bob Baker exclaims: ‘Greg, do you have a formal suit you can wear?’

Baffled and bemused by his question, I replied, rather sarcastically, that I did, and then, in the manner of a schoolboy, speaking to a particularly strict teacher, I said, almost sotto voce, ‘But why do you ask?’, just missing was the word ‘Sir’.

His argument was that, despite my youth and self-professed ‘hipster’ attitudes, I had to remain ‘above the artists’ in terms of persona. To cut a long story short, I acquiesced and turned up the next day wearing a Cecil Gee creation, complete with pristine white Oxford shirt and burnished black brogues.

Coffees and teas at La Gioconda often resembled mini-board meetings, and it was there that I first discovered that Baker was just using Press Presentations as a stepping-stone to ‘greater things’. The other thing I soon realised was that he was ultra-professional, but only in terms of dealing with erratic and often thuggish rock managers and acting as a suave maître d’ at high-level press receptions. When it came to ideas he was, in my book, out of touch.

Anyway, after these preliminary exchanges, which I must admit I found somewhat deflating and tedious, it was time for me to be introduced to the various agents, managers and star names that kept the company’s kitty happy.

The first time I met Giorgio Gomelsky, I thought I was in the presence of Grigori Rasputin, the mad mystic who had dominated the lives of the ill-fated Russian Royal Family, the Romanovs. His hair was greasy and wild, and he waved his hands around like some demented tic-tac man at the Derby. He had this habit of staring at you, and if something, no matter how outlandish, appealed to his aesthetic sense, he shouted ‘knockout!’

Born in the old Soviet Republic of Georgia, his early life saw the family travel extensively throughout Europe, eventually settling in Switzerland in the 1940s, which explained why by 1964 he had managed to get hold of a Swiss passport. He drove his Ferrari or Maserati or whatever it was like the wind – in fact his skill with the steering wheel was witnessed to good effect in the Mille Miglia, Italy’s answer to the Le Mans 24-hour endurance race.

Giorgio was manager and general all-round guru of The Yardbirds. His eye for talent was masterly, but this innate talent was negated by a complete lack of any normal business practice.

Here was a man who had discovered The Rolling Stones – he was the group’s first manager before the hustler that was Andrew Loog Oldham came sauntering in to ‘pinch’ them – and who later turned The Yardbirds into London’s number one cult band. And if that wasn’t enough he launched the career of the enigmatic and ethereal beauty Julie Driscoll – ‘The Face’. He was also a mass of contradictions, one minute waxing lyrical about art and the blues and the next minute arguing with Eric Clapton on the direction the band should take, with Clapton being the purist and Giorgio wearing his ‘we need to become more commercial to make money’ hat.

Maureen Cleave interviewed all the great and good of

British pop culture in the 1960s. Her page in the London Evening Standard became a must-read for any one embroiled in the mushrooming rock scene. She spoke with what used to be called a ‘cut glass accent’, was elegant to the point of perfection, and cultivated a close relationship with The Beatles. In fact it was during the interview with John Lennon that he came out with those famous or infamous – depending on your viewpoint – words in March 1966: ‘Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink. I needn’t argue with that; I’m right and I will be proved right. We’re more popular than Jesus now; I don’t know which will go first – rock ’n’ roll or Christianity. Jesus was all right but his disciples were thick and ordinary. It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.’

So, when it came to The Yardbirds being interviewed by Cleave, Giorgio Gomelsky – always a man to demand that he be the centre of attention – did his utmost to curb his more extravagant instincts.

Cleave was class, but as a young man with little experience of columnist headliners, she struck me as snooty and frankly up herself. ‘Are you in the group too?’ she asked me rather dismissively. ‘No,’ I replied sheepishly. ‘I’m with their publicity people.’

A wave of the hand dismissed me from the scene, and the interview began. Her attitude made me all the more determined to fight my corner. ‘I bet she wouldn’t treat Andrew Oldham like that,’ I said to myself.

My first organised media interview session was over, and I felt deflated. Cultural revolution was in the air, but none of this seemed to permeate through to the people with whom I was working. And my next ‘assignment’, a meeting with Georgie Fame’s manager Rik Gunnell, only reinforced this general feeling of being let down.

Even as a teenager, I was no shrinking violet, but Gunnell frightened me. He exuded gangster from every pore, and even his smile was creepy. Georgie Fame once described him as ‘a loveable villain’, but in my book there was nothing remotely ‘loveable’ about him!

Chelsea FC in the Swinging '60s

Chelsea FC in the Swinging '60s